Modal verbs are useful devices to evince the authors' stance concerning the propositional content (Biber et al., 1999; Palmer, 2001; Collins, 2009); therefore, these verbs can report on perspectivisation in introductions and conclusions. In this context, we expect that probability modal verbs entailing tentativeness will occur more frequently in introductions and necessity modals should appear more frequently in conclusions. Research on the use of modal verbs in these two sections of the research article has been conducted using corpus tools for text retrieval and analysis. Variation ratios will be evaluated using a log-likelihood test to determine the significance of variation according to whether specific modal meanings appear in the introductions or the conclusions.

Our main research questions are 'How does the use of modal verbs vary in the introduction and conclusion sections of scientific tourism research articles in terms of form and meaning? ' and 'How does the use of modal verbs vary in the introduction and conclusion sections of scientific tourism research articles in terms of the functions they fulfil? The present study examines modal verb meanings and variation in these verbs in a corpus of texts in the field of tourism. We use a compilation of article introductions and conclusions written in English and published in leading journals specialised in tourism studies. Modal verbs are important to evince the authors' stance concerning the propositional content (Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad & Finegan, 1999; Palmer, 2001). Variation ratios will be evaluated using a log-likelihood test to determine differences in significance between occurrences in introductions and conclusions.

Our conclusions will report, therefore, on the forms, meanings and functions of modal verbs in the sections analysed. Epistemic modality occurs more frequently in the introductions of engineering texts and less frequently in the corpus of tourism and linguistics respectively. Deontic modality is used more frequently in the linguistics and engineering introductions in this order and used less frequently in tourism introductions.

Dynamic is the second most frequent modal meaning and it is the most common in the corpus of tourism research articles. Deontic meaning is the third most frequent modal meaning, and this type also occurs more frequently in the corpus of tourism. We have been particularly interested in the use of modal verbs in introductions and conclusions. In this sense, even if this has not been our primary aim, we have detected disciplinary variation through the contrast between our findings and the findings of Alonso-Almeida and Carrió-Pastor in linguistics and engineering scientific papers.

In addition, in line with our main objective, we have identified variation in the use of modal verbs in introductions and conclusions of tourism research articles. Research has been conducted using corpus tools to obtain evidence from our sub-corpus of introductions and conclusions, as mentioned earlier. Direct visual inspection of the texts has also been vital to identify the meaning of the modal verbs in context. The fundamental role of the context in specifying the sense a particular modal verb entails has been mentioned in the literature (see Huschová, 2015; Alonso-Almeida, 2015a and the references therein). A modal verb may indicate an array of meanings, and therefore without these contextual cues, it would be unreasonable to expect an accurate categorisation of these verbal forms.

The plasticity of modal verbs makes them unique; however, it also challenges our ability to identify the meanings they involve each time. In addition to these senses of modal verbs, there is another aspect that cannot be achieved through an automatic interrogation of a computerised corpora, and this is the function these verbs fulfil in the texts in which they appear. Dynamic modality appears to occur more frequently in the conclusions of tourism research articles, as shown in Figure 4 above. The LL ratios in Table 2 indicate that the forms 'can', 'could' and 'will' are more likely to occur in conclusions. The modal 'may', however, appears more frequently in the introductions analysed.

From a pragmatic perspective, the use of more dynamic modals in conclusions may have a strengthening effect in communication as this modal meaning indicates factuality, and this information may be presented as a conclusion in this way. There is, however, an intention to mitigate the illocutionary force of the propositional content by using this modal type as facts rely on potentialities and abilities, which may eventually not show. This modal verb presents factual information, avoids blatant imposition of perspective, and prevents potential face-threatening acts (Brown & Levinson, 1987). As shown in Figure 4, dynamic modality is the most common modal device in the texts in both the introductions and the conclusions.

In the case of the latter, the number of dynamic modals exceeds the number of other modal meanings in the conclusions and introductions. Epistemic modals appear in the second position, with more cases registered in conclusions. The use of deontic modality is very common in the conclusion sections, with only a few more cases than the epistemic devices. In the introductions, deontic modality is not a recurrent element.

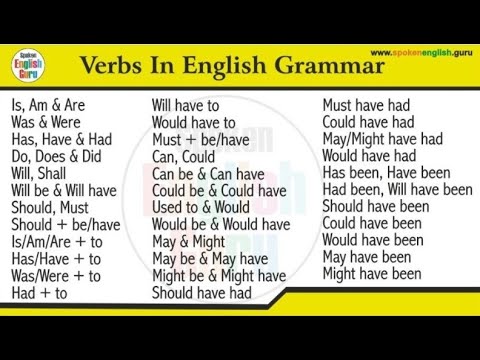

We shall comment on each modal type in the order of frequency. In this description, we use statistics based on the LL calculation of variation. The LL ratio works quite well for evaluating variation in small textual compilations, as in the case of our corpus of introductions and conclusions of research papers. In English, the modal verbs are used to express ability, possibility, permission or obligation. Each one of the modal verbs can be used to express one or more of these modalities. They can also be used to form the future tense in English and to make conditional sentences.

The verbs/expressions dare, ought to, had better, and need not behave like modal auxiliaries to a large extent, although they are not productive in the role to the same extent as those listed here. Furthermore, there are numerous other verbs that can be viewed as modal verbs insofar as they clearly express modality in the same way that the verbs in this list do, e.g. appear, have to, seem etc. In the strict sense, though, these other verbs do not qualify as modal verbs in English because they do not allow subject-auxiliary inversion, nor do they allow negation with not. If, however, one defines modal verb entirely in terms of meaning contribution, then these other verbs would also be modals and so the list here would have to be greatly expanded.

Finally, deontic modals appear to match exactly the goals of the introduction, namely a programmatic function, and those of the conclusion sections, namely a recapitulation function. In the case of the former, deontic modals represent meanings concerning promises of action in the paper and the expression of expectation arising from the revision of earlier literature on the topic. Along with dynamic modality, the pragmatic function of deontic modality seems to be the indication of authority, and therefore this type of modality may have a persuasive effect on readers.

In all these cases, the modal verbs 'can', 'must' and 'should' report on the desirability of the actions described in the propositional contents of the statements in which these verbs appear. The idea of improvement, as in above, remains strong in the use of these modal verbs in all these examples. These verbs indicate that it is essential for local tourism representatives of agents to take some actions to boost economic areas of tourist interest, which means that P done by A 'is better than' ¬P by A. It seems clear, therefore, that the pragmatic motivation of deontic modals results from a desire to suggest authority as this notion is strongly connected with credibility in science.

We have used a compilation of article introductions and conclusions written in English and published in leading journals specialised in tourism. These sections have been selected as they constitute two specific moments in the production of the paper. The introduction seems to have the clear function of assisting readers to read the article through the presentation of intentions, objectives and tentative conclusions.

The conclusion seeks to summarise the strengths of the paper with clear answers to the research questions presented in the introduction. This means that the viewpoints in the two sections must be different. The introduction, for instance, has a programmatic perspective with a focus on knowledge and expectations, and the conclusion may present more examples of authoritative voice after the analysis of the evidence than the introduction. In our corpus, the modal forms matching Nuyts' definition and, therefore, entailing epistemic meaning are 'may', 'would', 'can', 'could' and 'will' in this order of frequency in the introductions. This also means that all the epistemic modals detected have the evaluative dimension specified in Cornillie's characterisation of epistemic modality. The conclusions present the same forms to convey epistemic modality.

Figure 5 visually presents the significant variation in the use of epistemic modals in introductions and conclusions, and this is also seen in the LL values presented in Table 3. A small group of auxiliary verbs, called the modal verbs are only used in combination with ordinary verbs. A modal verb changes the other verb's meaning to something different from simple fact. Modals may express permission, ability, prediction, possibility, or necessity. In English, modal verbsare a small class of auxiliary verbs used to express ability, permission, obligation, prohibition, probability, possibility, advice.

The English modal verbs are a subset of the English auxiliary verbs used mostly to express modality (properties such as possibility, obligation, etc.). They can be distinguished from other verbs by their defectiveness and by their neutralization (that they do not take the ending -s in the third-person singular). The variation in the use of epistemic modality in the sections studied is meaningful. It was found that epistemic modality is more common in the conclusions than in the introductions. The main pragmatic function of epistemic modality is to signal mitigation of the propositional contents, and therefore the authors' commitment to the proposition is lower. In the specific case of conclusions, epistemic modals are deployed to hedge conclusions resulting from the interpretation of the analysed phenomena in the research articles.

Epistemic modality is also used to indicate the logical analysis behind the authors' argumentation. In general, the pragmatics of this type of modality in both sections is the manifestation of a lack of commitment to the information presented with the aim of avoiding imposition. Deontic modality is the least frequent of the three modality types. In the texts, deontic modality is realised by the modal verbs 'will', 'can' and 'would', and this deontic modal appears in the introductions and the conclusions of our corpus.

The definition of modality by some authors, such as Saeed , includes the notion of commitment of the speaker concerning the truthfulness of the given proposition, which may include gradation from likely probability to unlikely probability. In Gotti and Dossena's definition, there is the difference between modality and mood, the latter being of a morphosyntactic nature and reflecting aspects of the reality referred to in the proposition. An example would be the use of the imperative to express a command as opposed to the use of the subjunctive to indicate hypotheses regarding the possible realisation of the action described. In addition to the mode, other linguistic elements communicate modality as the modal verbs and some clitics, as highlighted by Palmer .

In short, modality can manifest itself both morphologically and with lexical mechanisms. The case of modal verbs, as affirmed by Aikhenvald , is considered halfway between the grammar and the lexicon. Modals are part of a verb phrase; they give more information about the main verb by qualifying it in some way.

Modals also have an effect on the grammar of the verb phrase; after a modal, the infinitive form is used. Some modals can be used with different time references, present, past or future; others are restricted to one or two time frames. Some modals can be used in negative expressions, others cannot, and sometimes when used in a negative expression the usage changes. The chart below summarizes the time frames that are possible with the modals and their most common usages.

In English, main verbs but not modal verbs always require the auxiliary verb do to form negations and questions, and do can be used with main verbs to form emphatic affirmative statements. (Neither negations nor questions in early modern English used to require do.) Since modal verbs are auxiliary verbs as is do, in questions and negations they appear in the word order the same as do. The negated forms are will not (often contracted to won't) and would not (often contracted to wouldn't). For contracted forms of will and would themselves, see § Contractions and reduced pronunciation above. Note that the preterite forms are not necessarily used to refer to past time, and in some cases, they are near-synonyms to the present forms.

Note that most of these so-called preterite forms are most often used in the subjunctive mood in the present tense. The auxiliary verbs may and let are also used often in the subjunctive mood. Famous examples of these are "May The Force be with you." and "Let God bless you with good." These are both sentences that express some uncertainty; hence they are subjunctive sentences. In academic writing, modal verbs are most frequently used to indicate logical possibility and least frequently used to indicate permission. Eight modal verbs are listed under each of the functions they can perform in academic writing, and are ordered from strongest to weakest for each function. Notice that the same modal can have different strengths when it's used for different functions (e.g., may or can).

In many Germanic languages, the modal verbs may be used in more functions than in English. In German, for instance, modals can occur as non-finite verbs, which means they can be subordinate to other verbs in verb catenae; they need not appear as the clause root. This for instance enables catenae containing several modal auxiliaries. The modal verbs are underlined in the following table. In many cases, in order to give modals past reference, they are used together with a "perfect infinitive", namely the auxiliary have and a past participle, as in I should have asked her; You may have seen me. Sometimes these expressions are limited in meaning; for example, must have can refer only to certainty, whereas past obligation is expressed by an alternative phrase such as had to (see § Replacements for defective forms below).

As a modal verb, "should" has many important uses in the English language. It's used to give advice, to express what's right, and to recommend an action. Also, it's used to make predictions, but ones that are more uncertain than those with the other modal verbs. Modal verbs are helping/auxiliary verbs that give additional information about the function of the main verb that follows.

What Are Modals And Their Uses They express attitudes such as ability, possibility, permission, and suggestion. All of these modal verbs must come before a verb to help express at least one of the modality examples listed above. In some cases, though they can be used to express more than one modality, but you'll see more on that in the following section.

So, let's take a look at some example sentences and highlight how the modal verb is expressing modality and adding more information to the verbs that follow them. In English grammar, a modal is a verb that combines with another verb to indicate mood or tense. A modal, also known as a modal auxiliary or modal verb, expresses necessity, uncertainty, possibility, or permission. For this reason some grammars consider also the verbs osare ("to dare to"), preferire ("to refer to"), desiderare ("to desire to"), solere ("to use to") as modal verbs, despite these always use avere as auxiliary verb for the perfect. Hawaiian Pidgin is a creole language most of whose vocabulary, but not grammar, is drawn from English. As is generally the case with creole languages, it is an isolating language and modality is typically indicated by the use of invariant pre-verbal auxiliaries.

The invariance of the modal auxiliaries to person, number, and tense makes them analogous to modal auxiliaries in English. However, as in most creoles the main verbs are also invariant; the auxiliaries are distinguished by their use in combination with a main verb. A greater variety of double modals appears in some regional dialects. In English, for example, phrases such as would dare to, may be able to or should have to are sometimes used in conversation and are grammatically correct.

The double modal may sometimes be in the future tense, as in "I will ought to go," where will is the main verb and ought to is also an auxiliary but an infinitive. Another example is We must be able to work with must being the main auxiliary and be able to as the infinitive. Other examples include You may not dare to run or I would need to have help. The first finding of this study is that dynamic modality appears more frequently than any other type in the introductions and conclusions.

Moreover, statistics reveal that the variation between these two sections is very significant in this respect, with overuse of dynamic modals in the conclusions. The function of these modals is to account for factual truth regarding the conditions of people and objects to fulfil an action, as well as the conditions for the action to occur. Dynamic modality, therefore, contributes to pragmatic strengthening in that the idea of authority is achieved by phenomena presented as factual truths rather than as suppositions.

Read the following examples and explanations carefully. We don't have enough room to look at every modal verb, but we can give you some examples so that you can see how different modalities are being expressed, and then you will be able to spot them for yourself in future. -,gamōtmaymögen, magmogen, magmögen, magmeie, meimagmå(må)mega, mámagum, magwissen, weißweten, weet? Witte, witweetvedvetvita, veitwitum, wait(tharf)dürfen, darfdurven, durfdörven, dörvdoarre, doardurf?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.